History of the farm

They say farming is in the blood – but anyone from a farming family knows that isn’t true.

It isn’t in the blood.

It’s in the marrow of your bones, in the skin of your fingers, cracked and raw from freezing nights in the lambing shed, from the stoop of your back from lifting heavy bales, from the depths of your soul trying to make it work, make a living, make a life.

There’s no quitting. There’s no giving in. When your farm is ripped from your grasp, your family home sold to make way for a new council estate. You your- self dust off. You move on. You make it work somehow.

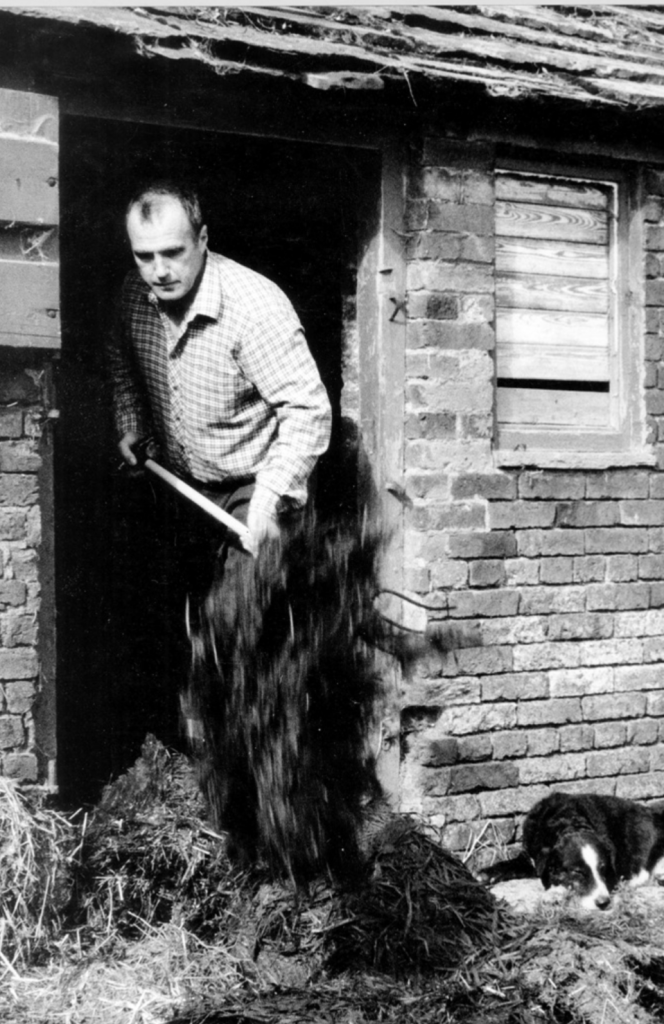

Roger Nicholson was 16 years old when life as he knew it changed forever.

He had spent a happy childhood at Bank End Farm in Worsborough, helping his Dad Charlie farm the land that had belonged to the Nicholson’s since 1650.

Since he could walk, he could farm. As a toddler, he made the farmyard his playground, adopting pet lambs and helping to bottlefeed the ones who needed it.

And by the time he was eight, he’d become quite the expert at driving the Shire horse, his small frame perched on the metal seat of the hay rake behind, clinging on to the reigns as it navigated across the hay meadows.

At just eight years of age he would rush home after school each day ready to milk two cows by hand.

In winter it was a particularly tough task, his hands already cold from the biting air chilled and chapped by the frost.

But even now, 70 years later, that smell of fresh milk can still catapult him back to a simpler time – when his knees were covered in scrapes from the many adventures that were offered a boy living in more innocent times.

Right back to when he was surrounded by the smells of home, his small head pushed into a cow’s side as he balanced on a three-legged milking stool and focused on the task at hand.

Roger was precious to his parents. Charlie and Irenie had three daughters, Olive, Shirley and Beryl, but longed for another boy, after their first son, Alan, died as an infant. They longed for a boy to carry on the tradition that the generations before had done.

Roger was born to take on the mantle of head of the family – continuing the historic family tradition of farming. While most children were learning the alphabet and simple sums, Roger had an extra curriculum to get right. He not only had to learn how to care for the animals but also the complicated business of farming – the stock and trade that came with being a cattle man.

By the time he was 13 years old, Roger knew in his bones he was exactly where he should be. He was never happier than when he was outdoors, with the animals under his care.

It was a balmy, summer’s day when he smelled smoke and realised disaster was in the air. Fire was no one’s friend but, to a farmer, fire could spell ruination.

On legs made strong from labour, Roger rushed towards the blaze and realised it was confined to a haystack just a few feet from one of the stock- yards. He could hear the panicked calls of the animals inside and as the building filled with smoke and realised that he had to act.

In a heroic moment, that was later reported in the local newspaper, Roger rushed into the burning building and saved all the animals, leading them to safety through the acrid smoke, and away from the flames.

In many ways, Roger led a varied and happy life at his family farm in Worsborough Dale – but the crushing news that it was being compulsory purchased came as a shock to the family.

They stood to lose not only their home but also their land and their livelihood. The council was building a new housing estate – and the land they had chosen was the Nicholson’s.

They were offered a derisory settlement, £60 an acre. In the weeks that followed they began to box up a lifetime of memories, preparing to leave the land Roger had once imagined himself growing old upon.

But Charlie Nicholson was never a defeatist – and with pragmatism that

he passed down to his son, he realised that, in reality, the compulsory purchase could be seen as an open door. They’d been given a chance to try a new challenge.

He was thrumming with excitement when he told his family his plans to move the Nicholson’s to a new farm – and he had his sights firmly set on one place.

Cannon Hall Farm in Cawthorne was a historic, 126 acre holding that sat in the Pennine foothills, the home farm to a historic house. It had the potential to be great – offering not only beautiful landscapes but also space to grow.

Despite the heartbreak of a forced move, Charlie became convinced that Cannon Hall Farm was the Nicholson’s destiny. He was a pragmatic businessman who lived by a firm set of rules. He instilled honour and work ethic in his children and his peers. He was a proud farmer, competing in agricultural shows and winning awards for his prized beasts.

He was not a man to change his mind once he’d made it – nor was he one to embark on frivolous risks.

Cannon Hall Farm was going under the hammer; the aristocratic family who’d lived there had long gone. The manor house had become a public museum run by the council but the land was available.

Charlie took his life savings and headed to the auction. He’d set himself a limit – he’d sworn to himself the most he could stretch to was £7,000 – a small fortune at the time and representing many years of hard-fought savings.

In the auction room, the atmosphere was electric. He sat on a chair, heart racing, hands in a nervous sweat gripping the paddle.

Bidding leapt forward at a rapid pace.

£3,000.

£4,000.

£5,000.

He hadn’t placed a single bid. As he glanced around him, he saw rabid determination on his rivals faces and he felt a sinking moment of despair.

£6,000.

£7,000.

Going, going…

Charlie had still not placed a bid. He’d lost the auction without placing a single bid.

The thick wool of his trousers scratched as he used them to wipe his damp palms, and with seconds to spare, Charlie took a leap of faith.

He bid £7,100 – over his own budget, breaking his own rule. But the hammer dropped and it was official.

Cannon Hall Farm became a part of the family. And for generations they would become not just custodians of the land but advocates for it too.

And so the family embarked on their new challenge – but sadly Charlie would not live long enough to see if his big dreams would pay off.

Within twelve months of moving to Cannon Hall Farm, Roger returned home from school to be told his dad had died suddenly.

He was only 16 – grieving, shocked, and scared but he had to step into the role as head of the family, establishing a completely new business and making it work.

It was a crushing burden. There had been such buoyant excitement and plans for the future – but Charlie had been the larger than life character driving it forward and without him, Roger felt unmoored.

He knew he had to manage the farm as Charlie would have wanted – but it was a daunting task for a teenager still at school.

Roger poured himself into the business – he was well-liked in the farming community with many of Charlie’s old friends and neighbours offering him assistance.

And by the time he was 18, he’d established Cannon Hall Farm as a viable business. It was self sustaining. Charlie’s dream was safe.

It was at a Young Farmer’s Dance, in the depths of winter, that Roger would encounter the next pivotal moment of his life.

It was a miserable year, thick with snow, and the Halifax young farmers event was a sorry affair.

Hardly anyone had turned up due to the weather – but the few that had were determined to have a good time.

They decided to play a risqué́ game where the girls had to remove their stockings. It was then that Roger met Cynthia – when he cheekily asked if he could help her in putting them back on.

Cynthia was never one to beat around the bush – and gave him a withering look and a categorical no thanks! But it was the opening Roger needed and, by the time they’d left, he’d arranged another date with the woman who would eventually become his wife.

They lived for a blissful few years at Cannon Hall Farm – cash poor but wealthy in experience and spirit.

And then: children. Three boys who came within four years of each other, to carry on the legacy.

Roger continued his tradition of milking cows, but just one now, a ‘house cow’. They called it the ‘Pantomime Cow’ due its comical, accentuated bone structure. And he’d always make sure there was fresh milk for the boys to wake up to, still frothy and warm for breakfast.

It wasn’t long before Richard, Robert and David were helping out on the farm too – helping get the turkeys ready for Christmas and selling them to locals in the village of Cawthorne.

The children’s job was to pluck the birds, transporting them around to the room where they were to be processed. Times were tough and there wasn’t much money around so the ancient, battered Silver Cross pram that Cynthia had so lovingly pushed her children around in was thrown into service as a turkey carrier. It was used in the farmyard, for various jobs for many years.

It was hard, cold work. Auntie Flo told dirty jokes that always had everyone chuckling when she finally managed to stop laughing for long enough to deliver them.

Fred was a big strong fella who wore checked shirts, had a huge beard and eyes that sparkled with mischief. He looked like a lumberjack and lived on the moors above Halifax and would come to help at Christmas. The children’s favourite game was to pretend to be turkeys, queuing up for Fred to pick them up, using the house radiator as a ‘plucking machine’ as they screamed with laughter.

When the turkeys were sold on Christmas Eve and the battered old tin that served as a cash box was full of money, Roger would head off for some last minute shopping and always made sure to come home with a big gift from Santa.

A kid’s snooker table, table football, or the very favourite, a table tennis table that was used for many years and led to Robert being ranked in the top 16 boys in Yorkshire and Robert and Richard representing Barnsley at junior level.

Christmas for the Nicholson’s was about coughing as feathers filled the air, hot steaming breath in the chilly atmosphere and dressing the birds with sore fingers, aching from the cold.

But, best of all, Christmas was about precious memories of people long gone, gilded with nostalgia and the hope that those memories will be passed on to

the next generation. That the lessons learned, the laughter, hard work and events that shaped the childhood of the Nicholson brothers would become a perfect storm of circumstance that would eventually save Cannon Hall Farm and preserve it for future generations.

As small children, Robert and David were always thinking of get-rich quick schemes to add to the coffers – the grand old house next door was a museum and country park, bringing in thousands of visitors.

Picture the scene, two small boys, grubby from plenty of adventures, wearing home made shorts and ankle socks. Robert had been born with charm in spades and was always one to spot an

opportunity – so he convinced David to carry a battered cardboard box with an unwitting chicken inside.

He’d wait for a likely looking passer by, preferably a family with children, then approach and confidently ask: “would you like to stroke a baby chicken for 2p”?

If the answer was yes then David was under strict instructions to then produce the said chicken from the box.

Robert would be the one to take the money and shove it down his sock. It is a source of mystery as to where those precious 2ps went – because poor David never did seem to get his share.

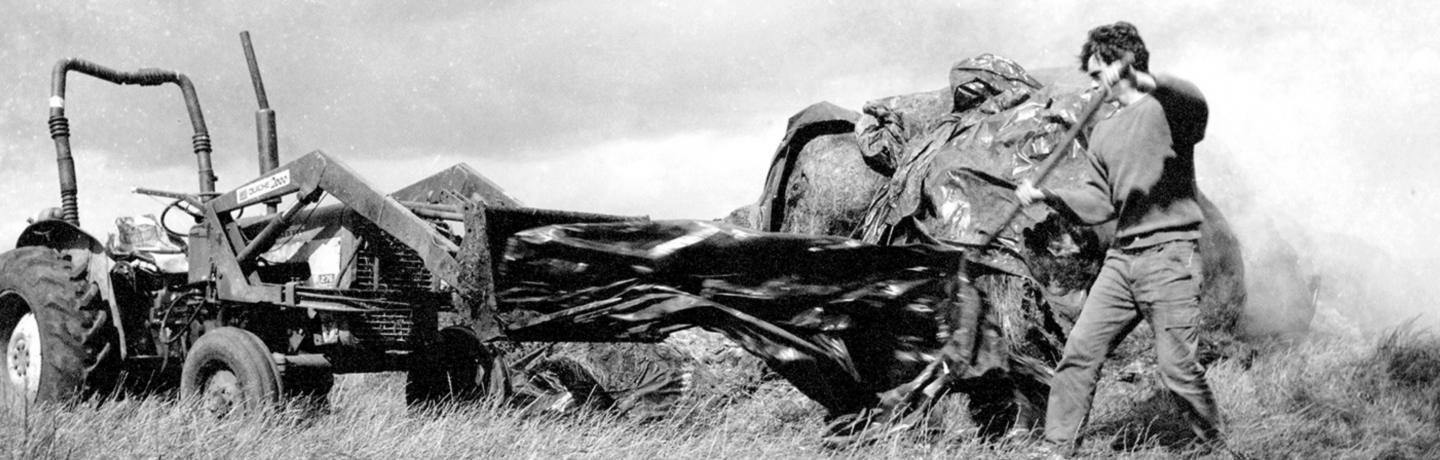

But by the mid-1980s the honeymoon period was over. Roger had struggled to make the business work – he’d worked as hard as he could, but poor market values on produce meant he’d never made a profit of more than £700 in a year. The overdraft was building year on year.

Incomes were falling, the bank was no longer willing to lend and the pressure was building.

He was heavily in debt and the bank had called a meeting. He felt despair and disappointment – his teenage sons were at college and he’d always hoped that the business could sustain them all, and give them jobs when they left.

He had wanted to carry on Charlie’s dream of the Nicholson farming legacy – but it had become very clear that being ‘just’ farmers was not working.

Roger had visited a handful of farms around the UK – like Chatsworth and Cotswold Farm Park which had opened to the public – and he thought he saw a way forward. Could Cannon Hall Farm achieve the lofty heights of Chatsworth and become a visitor attraction that people would actually pay to visit?

The bank manager had called in a special agricultural advisor and Roger set out his plans – which involved selling some of the farm buildings for housing and redeveloping others.

He had carefully mapped out a vision for the future which would give his boys secure jobs to come home to. His vision – to open the farm to the public and build the business into a tourism venue.

But the bank’s reply was stark and not designed to spare Roger’s feelings.

He’d never been able to support his

wife or his family, they said. He should

just sell up and get a different job while

he still had equity in the business.

He gathered together his papers and

walked out of the bank wondering if

they might possibly be right.

Roger faced a difficult situation – but he wasn’t about to give up. He didn’t want to be the generation that ended the Nicholson legacy.

He went to other banks, dogged with determination, until he found one that bought in to his vision.

He scraped together money for a few small improvements and the farm opened to the public for the first time on Good Friday, 1989.

Roger took £100 on that first day – an absolute fortune compared to his precious income levels – and never looked back.

It was the trigger that would end up becoming the catalyst for change – and Roger recognised that tourism was their future.

The ramshackle farm buildings became a firm favourite with local families, who loved the experience of feeding goats and lambs. They used an old farm building as a tearoom, with Cynthia baking her now famous scones for visitors to enjoy.

The early years were tough – and money was tight but Roger was fearless in his programme of reinvestment. Cannon Hall Farm transformed from a small, mixed family farm – to a visitor attraction with a working farm that was bigger than ever.

The boys grew up and married. Had children and looked to the next generation. Business was good. Visitor numbers were growing. They had a handful of employees and the future was secure.

They added adventure playgrounds and a farm shop.

Every time they took a risk and invested in the future, turnover, jobs and visitors increased.

Around ten years ago they embarked on a huge investment programme in the farm. It was a radical scheme and involved yet more borrowing. First came the iconic roundhouse, then a new £1.5 million farmyard, the demolition of the existing farmyard and the opening of the Hungry Llama indoor play.

They developed the very first farm visitor centre of its type in the world – one that allowed visitors to watch with the farmers during their day to day work – which can be as varied as assisting in a birth, milking, shearing or tractor work- from the safety of a viewing platform.

And 30 years after that first vision, Roger succeeded in not only creating jobs for his three sons…but in building a multi-million pound tourist attraction that employs over 270 local people.

Roger is now 76 years old – but he’s in the barns every single day – training the next generation of farmers and educating visitors to help them understand how important British farming is.

And he even has his own fanbase, a new generation of visitors that watch his series of live online broadcasts, led by his sons, educating people about being a farmer and what it entails.

His hard work was rewarded last year, when the farm was named Best Large Visitor Attraction in the White Rose Awards – and by landing a deal with a TV production company that saw Cannon Hall Farm be showcased to millions of people through the Channel 5 TV show Springtime on the Farm.

Farmer Roger has his legacy – the Nicholson’s have kept the treasure that is Cannon Hall Farm safe for the next generation.

He’s certainly not ready for a quiet retirement either with ambitious plans in the pipeline for further expansion Roger the businessman farmer is still leading the way in rural diversification – and creating childhood memories for a new generation as he does so.